Test. Evaluate. Learn. Innovate. Repeat – Train. Launch. Live. Work. Land.

The United Kingdom’s fascination with spaceflight began long before the Space Age. The concept of interplanetary travel captured the imagination of British scientists, engineers, and visionaries in the early 20th century. This growing interest led to the establishment of the British Interplanetary Society (BIS) in 1933, one of the world’s earliest space advocacy organizations. The BIS played a pivotal role in promoting space science and engineering, with members such as Sir Arthur C. Clarke, a renowned science fiction writer, futurist, and the visionary behind the concept of geostationary telecommunications satellites. His work would later influence the development of even today’s satellite communications, shaping the foundation of global connectivity.

During the pre-war years, British scientists and engineers actively discussed and theorized methods of space travel, even developing early conceptual designs for lunar landers and interplanetary spacecraft. However, significant progress in rocketry was not made until World War II, when nations began advancing missile technology for military applications.

Following the end of World War II, Britain, like other Allied nations, sought to acquire Germany’s advanced rocketry knowledge. Many German scientists and engineers who had worked on the V-2 rocket – the world’s first long-range guided ballistic missile – were recruited to aid British technological development.

Britain was among the first nations to conduct post-war tests on captured V-2 rockets, launching them as part of Operation Backfire in 1945, just six months after the war in Europe ended. These tests provided critical data on rocket propulsion, aerodynamics, and guidance systems. By 1946, British engineers had already begun conceptualizing and drafting blueprints for a crewed suborbital spacecraft, demonstrating early ambitions to enter the new frontier of human spaceflight.

The launch of Sputnik 1 by the Soviet Union on 4 October 1957 marked the beginning of the Space Age. As the first artificial satellite to orbit Earth, Sputnik’s success shocked the world and triggered an intense competition between the United States and the Soviet Union, later known as the Space Race.

At the time, Britain was seen as the only other nation, aside from the US and USSR, with the scientific expertise and industrial capacity to develop and launch spacecraft. The UK’s Blue Streak ballistic missile program, initially developed as part of the country’s nuclear deterrent, had the potential to serve as the foundation for a British space launch vehicle. Many expected Britain to take the next step toward launching its own satellite and establishing a national space program.

However, despite Britain’s advanced rocketry capabilities, Prime Minister Harold Macmillan was reluctant, at best, to commit to an independent space program. Even after meeting Yuri Gagarin on 14 July 1961 – just months after he became the first human in space – Macmillan maintained a cautious stance. While he acknowledged Gagarin as the “Columbus of the Space Age,” he dismissed calls for the UK to develop its own spaceflight initiatives. Instead, he accepted a US offer to launch British scientific satellites, a decision that reflected Britain’s pragmatic approach to space policy.

This reluctance set the tone for the UK’s space strategy in the following decades: rather than investing in independent human spaceflight programs, Britain focused on scientific research, satellite technology, and international collaboration. It wasn’t until May 1991 that the UK reached a significant milestone in human spaceflight, when Helen Sharman became the first British astronaut, first Western European woman in space, the first privately funded woman in space, and the first woman to visit the Soviet space station, Mir.

Her historic mission underscored Britain’s capability to contribute to global spaceflight, even without a national human spaceflight program.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Britain made major strides in satellite technology. The Ariel program, a collaboration with NASA, saw the launch of six research satellites, making Britain the third nation to have an operational satellite program after the US and the USSR. This partnership laid the foundation for a strong UK-US space alliance that continues today.

In 1971, Britain achieved a significant milestone with the launch of Prospero X-3, the first and only British satellite launched on a British rocket. The satellite was carried into orbit aboard the Black Arrow rocket, which had been developed as part of a government-funded program. Despite the success of Prospero, the UK government canceled the Black Arrow program shortly afterward, shifting its focus away from independent launch capabilities.

Although Britain moved away from rocket development, it continued to play a crucial role in European space efforts. The UK provided the first stage of the Europa rocket, based on its Blue Streak missile. While Europa faced several technical difficulties and was ultimately abandoned, the Blue Streak stage consistently performed successfully in every test flight.

In the following decades, Britain cemented its reputation as a leader in satellite design and manufacturing, focusing on uncrewed space exploration and commercial satellite initiatives. Unlike other major spacefaring nations, Britain never established a national astronaut corps. Instead, British-born astronauts such as Michael Foale (a NASA astronaut and the first Briton to perform a spacewalk) and Tim Peake (the first government-funded British astronaut to serve aboard the ISS as part of ESA) flew under the banner of foreign space agencies.

The British government only began funding the International Space Station (ISS) in 2011, more than a decade after its construction began, reflecting the country’s historically cautious approach to space investment.

As public interest in spaceflight grew in the UK, efforts to establish a National Space Centre began in the 1980s. Originally envisioned as a research facility with public access, the idea was first proposed by Professor Alan Wells and Professor Ken Pounds of the University of Leicester. However, due to lack of funding, the plan was not pursued.

In 1995, a revised proposal was put forward by Professor Alan Wells, Professor Alan Ponter, and Nigel Siesage, this time focusing on the creation of a museum and educational centre. Funding was secured from the Millennium Commission, covering half of the £52 million cost, with additional contributions from Leicester City Council, the University of Leicester, the East Midlands Development Agency, and BT, alongside corporate sponsors such as Walkers, the Met Office, Omega, BNSC, and Astrium. Originally named the National Space Science Centre, the name was shortened in December 2000 for marketing purposes.

On 30 June 2001, former NASA astronaut Jeffrey A. Hoffman officially opened the National Space Centre to the public. The centre quickly became one of the UK’s leading space attractions, welcoming 165,000 visitors in its first five months—exceeding expectations by 25%. In 2002, it was named Museum of the Year by the Good Britain Guide.

At its launch, the centre became home to over 60 scientists and astronomers working on cutting-edge space research within the Space Science Research Unit (SSRU). Today, the National Space Centre remains a key institution for space education and public engagement, inspiring future generations to explore the final frontier.

As you journey into the city, no matter which route you take, your eyes will be drawn to the striking 42-metre-high Rocket Tower at the National Space Centre. This iconic structure, a beacon of Britain’s space heritage, stands tall against the skyline, offering an exciting preview of the wonders within.

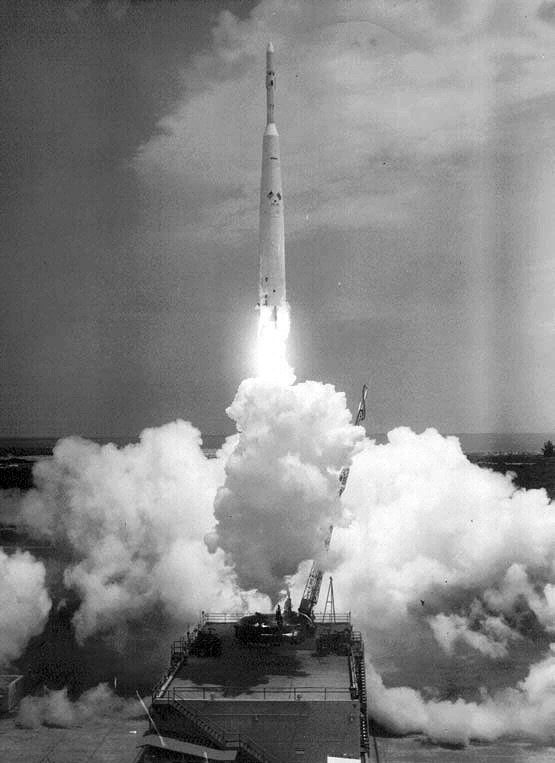

At the heart of the Rocket Tower are two legendary rockets: Blue Streak and Thor Able, which played a crucial role in the early days of space exploration. These towering artefacts serve as a testament to the UK’s contributions to rocket technology and global spaceflight. Visitors can also explore the Gagarin Experience, an immersive tribute to Yuri Gagarin, the first human in space, as well as marvel at an Apollo Lunar Lander, a symbol of humanity’s greatest achievement—the Moon landings. One of the most treasured artefacts inside the tower is a real Moon rock, a fragment of another world, offering a tangible connection to humankind’s journey beyond Earth.

The Rocket Tower’s design is as remarkable as the exhibits it houses. Clad in high-tech ETFE (Ethylene Tetrafluoroethylene) “pillows”, its semi-transparent structure allows natural light to filter through, creating a futuristic aesthetic that complements the Centre’s cutting-edge themes. This unique material, also used in modern architectural marvels like the Allianz Arena in Germany and the Eden Project in Cornwall, provides both insulation and durability while giving the tower its distinctive, space-age look.

Inside, the four exhibition decks take visitors on an inspiring journey through space history. The first deck delves into the Space Race, chronicling the intense rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union that drove early space exploration. Moving upwards, the next level explores the history of rocketry, from ancient fire-powered projectiles to the advanced propulsion systems that have carried humanity beyond our planet. Further exhibits focus on Britain’s own Space Race, highlighting key moments in UK space history, from the development of the Black Arrow rocket to modern satellite technology.

More than just a display of artefacts, the Rocket Tower is a living story of space exploration, immersing visitors in the challenges, triumphs, and innovations that have shaped our journey to the stars. Whether you’re gazing up at historic rockets, stepping into the world of cosmonauts and astronauts, or standing before a fragment of the Moon itself, the tower offers an unforgettable experience for space enthusiasts of all ages.

As you enter the main exhibit hall, the Home Planet Gallery at the National Space Centre stands out as a breathtaking and immersive exhibit dedicated to exploring the wonders of Earth, our only home in the vast cosmos. From the mesmerizing blue oceans and lush green forests to the swirling storms and shifting landscapes, this gallery offers visitors a unique perspective on our planet as seen from space.

As we marvel at the beauty of Earth, we are offered the opportunity to acknowledge the challenges it faces. Human activity – through deforestation, pollution, climate change, and resource depletion – and how it is reshaping the delicate balance of our environment, is shown on giant screens for all to see.

The Home Planet Gallery not only showcases the stunning splendor of Earth but also educates visitors on how human actions are impacting the planet and, most importantly, what we can do to protect it.

Modern space technology plays a crucial role in monitoring the health of our planet. The Home Planet Gallery then goes on to highlight how satellites provide scientists with vital data about Earth’s atmosphere, oceans, and land, and how these satellites help us:

Track climate change by measuring rising global temperatures and shifting weather patterns.

Observe ocean currents and ice cap melting, crucial in understanding sea-level rise.

Monitor deforestation and agricultural trends, ensuring better land management.

Detect urban expansion and air pollution, helping governments plan for sustainable cities.

Predict natural disasters such as hurricanes, wildfires, and earthquakes, saving lives and resources.

By analyzing satellite data, scientists can develop strategies to reduce environmental harm, anticipate global challenges, and ensure a healthier future for generations to come.

The Home Planet Gallery is not just about learning—it is the first stop on my visit that is solely about experiencing the wonder of Earth through interactive exhibits, that pursues the goal of making science engaging and fun. Visitors can:

Step into the Video Booth – Immerse themselves in satellite imagery and time-lapse footage of Earth’s changing landscapes. Witness the beauty of coral reefs, rainforests, and glaciers—and see firsthand how they are evolving over time. The exhibit also comes with the challenge of interpretation – understanding whether changes are part of long-term natural patterns or the result of accelerated human activities.

Chase Fish on the Interactive Floor – Engage with a playful and educational exhibit that demonstrates how climate change and human activities affect marine ecosystems. Learn how overfishing and rising ocean temperatures are reshaping underwater habitats.

Make Your Own Pledge – Before leaving the gallery, take part in an inspiring activity where visitors can commit to small, everyday actions that make a big difference for the planet. Whether it’s reducing plastic use, conserving energy, or planting trees, every pledge counts toward preserving Earth for future generations.

The Home Planet Gallery is more than an exhibit—it’s a call to action. As visitors explore the wonders of Earth from space and learn about its environmental challenges, they are encouraged to become stewards of the planet. How can we reduce our carbon footprint? What actions can we take to protect endangered ecosystems? How do space technologies help us create a sustainable future?

The answers to these questions lie in education, innovation, and action. The future of our Home Planet is in our hands, and together, we can ensure it remains a thriving, vibrant world for generations to come.

At this point in the article, I find myself welcoming the fact that moving freely around the National Space Centre is nearly impossible – thanks to the sheer number of school children on tours and trips. Seeing the next generation so engaged and enthusiastic is truly satisfying, leaving me with a smile throughout my visit.

Stepping into the Into Space gallery at the National Space Centre we experience the wonders of human space exploration like never before. This immersive exhibit brings you face-to-face with astronauts, spacesuits, and the incredible technology that has allowed humanity to reach beyond Earth’s atmosphere and venture into the vast unknown.

From the earliest days of the Space Race to the modern era of international cooperation on the International Space Station (ISS), the Into Space gallery explores the pioneering spirit, scientific breakthroughs, and personal sacrifices that have shaped our journey into space.

One of the most exciting features of the Into Space gallery is the walk-through mock-up of the Columbus Module—a full-scale replica of the European science laboratory aboard the International Space Station. This hands-on experience offers a rare glimpse into the cramped and high-tech environment where astronauts live, work, and conduct experiments in microgravity.

Inside, there is the opportunity to learn about:

Cutting-edge research in space – Discover how astronauts study topics like medicine, materials science, and plant growth in microgravity.

Daily life aboard the ISS – From sleeping in a floating sleeping bag to eating specially prepared space food, find out how astronauts adapt to life in orbit.

Technology that supports long-duration missions – Learn how water recycling, oxygen generation, and radiation shielding keep astronauts safe on long spaceflights.

And of course, you’ll finally get the answer to one of the most frequently asked questions at the National Space Centre; How do astronauts go to the toilet in space?

The Into Space gallery is home to extraordinary artefacts from some of the world’s most famous astronauts.

Helen Sharman’s actual Spacesuit & Launch Couch – Who made history in 1991 as the first Briton in space. Here, you have the opportunity to learn about her groundbreaking journey aboard the Mir Space Station, and how she paved the way for future British astronauts.

Buzz Aldrin, the second of the first two humans to set foot on the Moon during Apollo 11 in 1969, has visited the National Space Centre. This Constant Wear Garment was worn by Buzz Aldrin during training for the historic Apollo 11 mission. It is identical to the one that he wore during his flight to the Moon in 1969.

The Apollo Constant Wear Garment (CWG) was worn underneath flightsuits and the spacesuits that the crew wore inside the Command Module. This one-piece underwear was designed to keep the wearer comfortable. It helped to absorb sweat, as well as to hold the biomedical instrumentation system in place.

Also on display is the Sokol KV-2 emergency space suit worn by British ESA astronaut Tim Peake during his Principia mission to the International Space Station (ISS). Developed by RD & PE ‘Zvezda’, all cosmonauts wear this suit during the launch of their mission into space and again during their return to earth. The Sokol suit was developed after three unsuited cosmonauts asphyxiated on the Soyuz 11 mission in 1971 when their descent module depressurised during the return to Earth. The suit is connected to the spacecraft’s life support systems and provides approximately two hours of oxygen and carbon-dioxide removal in the event of a cabin depressurisation.

Many astronauts have graced the halls of the National Space Centre, sharing their experiences and inspiring future generations, and as you explore Into Space, you will hear firsthand stories of spacewalks, rocket launches, and life beyond Earth.

Also on display is the EVA spacesuit used during the filming of Ridley Scott’s movie, ‘The Martian’. Worn by actor Matt Damon and various stunt performers, it was used with a rigging system to simulate floating in space.

The costumes used in the film were designed to be accurate reflections of the sort of spacesuits that might be used in a near-future Mars mission. Academy Award winning costume designer Janty Yates worked with NASA and Scott to ensure that this Extra-Vehicular Activity (EVA) spacesuit worked for the film, but also imagined the future of NASA spacesuit design. Based loosely on the EMU spacesuits that NASA have used on the International Space Station, the suit is a less bulky, more streamlined design.

Behind these various suits and astronaut artifact displays, at what is essentially the entrance to the Into Space Gallery itself, is the Orlan DMA EVA spacesuit, one of the most successful spacesuit designs ever.

First used in 1977, this Russian designed suit has been continually modified in the years that have followed – with later models used aboard the International Space Station. The National Space Centre’s Orlan spacesuit is an Orlan DMA Extravehicular Activity (EVA) Spacesuit (serial #3). It is one of three prototypes manufactured by the Russian company, Zvezda, and was used in testing for the spacesuits worn on the Mir space station. In total only 28 Orlan DMA were ever made; 16 for training and testing, and 12 for spaceflight.

When looking up from the astronaut spacesuits, suspended from the ceiling is a Gemini TTV-2. The capsule is one of only two Tow Test Vehicles designed to test the possibility of a runway-style landing for the Gemini spacecraft. The capsule had a kite-shaped flexible wing attached, allowing the pilot to fly to a controlled landing. The vehicle displayed here, was flown by test pilot Jack Swigert. His selection as an astronaut was owed in part to his bravery and skill demonstrated in the TTV-2. He later achieved fame as the Command Module Pilot on the ill-fated Apollo 13 mission.

The Into Space gallery is more than just a museum—it’s an interactive experience designed to bring the adventure of space exploration to life. Visitors can:

Operate a robotic arm like the Canadarm2 used on the ISS for satellite repairs and cargo transfers.

Test your reflexes in a spaceflight simulator and see if you have what it takes to become an astronaut.

Experience microgravity simulations that show how everyday tasks – like drinking water – changing clothes in space.

The Into Space gallery is a tribute to the courage, innovation, and determination of astronauts and space scientists. It celebrates the past, present, and future of human spaceflight—from the early days of the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo missions, to the modern era of space stations, Mars rovers, and the Artemis program aiming to return humans to the Moon.

The Wonders of the Universe await you in the next immersive and interactive exhibit at the National Space Centre. From the birth of the cosmos to the search for extraterrestrial life, this gallery takes you on an awe-inspiring adventure through space, time, and the biggest mysteries of existence.

For centuries, humans have gazed at the night sky, wondering: Are we truly alone?

In this exhibit, you in essence, get to decide. Inside, you can your vote in an interactive debate on whether life beyond Earth exists, with help from the latest discoveries in exoplanet research, the conditions needed for life, and how scientists are using telescopes and probes to search for habitable worlds.

Ever wondered what happens if you fall into a black hole? Could wormholes be a shortcut through space-time? To help you navigate the questions posed by the exhibit, you can:

Take a virtual journey through a wormhole and discover the mind-bending theories of Einstein’s relativity.

Witness the Big Bang itself! Travel back 13.8 billion years to experience the birth of the Universe in a stunning visual recreation.

Explore the concept of time travel and how space-time warps in the presence of massive cosmic objects.

The Wonders of the Universe exhibit blends science with interactive fun and hands-on exploration. It asks you, like most of the National Space Centre does upon entry and throughout… Are you ready to explore the Universe? Your journey starts here.

Visiting the UK’s National Space Centre in July 2024, I feel I can say with some confidence that Britain is on the cusp of its own groundbreaking achievement in aerospace, as the nation prepares to launch a satellite into orbit from its own soil for the first time. This milestone marks a significant leap forward in the UK’s space ambitions, paving the way for a homegrown satellite launch industry and bolstering the country’s presence in the global space sector.

However, the exact location of this historic launch has yet to be determined. Several emerging space ventures, backed by the UK Space Agency, are currently competing to be the first to send a satellite into orbit from British soil, each employing different technologies and launch methods.

One of the leading contenders is located in Cornwall, where Virgin Orbit plans to use an innovative air-launch system. A modified jumbo jet will carry the LauncherOne rocket to an altitude of 35,000 feet before releasing it, allowing the rocket to fire its engines and propel its satellite cargo into orbit. This pioneering approach, which offers flexibility and the ability to launch from various locations.

Meanwhile, rival spaceports in Scotland are preparing for more conventional vertical rocket launches. The Sutherland spaceport, located on the country’s northern coast, and the Shetland spaceport, situated on the remote island of Unst, are both aiming to deploy two-stage rockets directly from the ground to orbit. These launches, highlight Scotland’s growing role in the UK’s space ambitions, with both sites positioning themselves as key players in the emerging small satellite launch market.

Beyond these frontrunners, additional plans have been proposed for spaceports in Scotland at Campbeltown, Prestwick, and North Uist, expanding the UK’s future launch capabilities. Wales is also entering the race with an innovative approach. B2Space, based in Snowdonia, has unveiled a unique concept involving a helium-filled balloon. This dirigible will ascend to an altitude of over 20 miles before deploying a small rocket, which will then ignite and carry its satellite payload into orbit. This method offers an alternative to traditional launch systems, reducing costs and minimizing environmental impact.

With multiple projects in development and competition heating up, the UK is positioning itself as a key player in the commercial space industry. Whichever site claims the first launch, this new era of British spaceflight promises to create opportunities for innovation, economic growth, and a stronger presence in the global space sector.

With the UKs future in space exploration seeming positive, it’s clear the National Space Centre strives to captivate and inspire visitors through engaging exhibitions, showcasing iconic artifacts and compelling stories that celebrates remarkable scientific achievements. By bringing the past, present, and future of science to life, it encourages curiosity, creativity, and discovery in people of all ages. Exactly what is needed.

The ever-growing collection serves as a lasting testament to the UK’s pursuit of knowledge, documenting groundbreaking advancements in space science, and technology. From pioneering inventions to cutting-edge research, the National Space Centre offers a unique window into the innovations that have shaped our world and continue to drive progress.

Reluctance over.