The British fascination with space, and for the universe as a whole, seems particularly significant as it is evidently Humanity’s least explored frontier. But Britain’s effort in space exploration has been rather quiet in its successes, it has never put a man on the Moon, or for that matter, anywhere near it, of planting a human’s footsteps on a celestial body outside of our native, already colonised planet Earth. Although at one stage, that in itself wasn’t such an unlikely sounding prospect.

During the Second World War, Britain pioneered the use of jet engines and between 1943 and 1949 began developing and building the first commercial passenger jet, the ‘De Havilland Comet’ alongside the ‘Vampire’ (built coincidentally at the site of my University campus, the former Hatfield aerodrome) which first and foremost, albeit rather briefly, established Britain as the world’s foremost aircraft maker, and secondly, cemented itself as a leader in rocket development outside of the US and USSR respectively. A year before the end of the Second World War, Germany had successfully launched the world’s first long-range missile – the V2 rocket, which became the first artificial object to cross the boundary of space with the vertical launch of the MW 18014 on the 20th June 1944, which soon led to them being assigned to their primary use; to attack Allied cities as retaliation for the Allied bombings against German cities. But defeat lead to the country’s remaining rockets being seized by the US, the USSR and Britain. The eventual President of the British Interplanetary Society, Ralph Smith, proposed adapting the V2 to carry humans into space, but the government rejected his plans due to limited, if not depleted post-war funds.

“The design was totally practical… All the technology existed and it could have been achieved within three to five years.”

David Baker – former NASA engineer, on Ralph Smith’s manned-rocket design

image credit: Roger Violett/Getty Images

But, in 1955, ten years after the end of the Second World War, British scientists took what they had learned from the German V2 and began developing the ‘Blue Streak’ intermediate-range ballistic missile, which had a range of about 2,500 miles. The ‘Blue Streak’ eventually found a role as the first stage of the Europa satellite launch vehicle, a rocket built-in collaboration with several other European countries. The UK continued to work independently, launching the ‘Skylark’ rocket in 1957, but it too would soon be incorporated into the European space programme. The future of British space exploration was to be as the partner of larger, better funded organisations.

image credit: Deutsches Museum at Schleissheim, Munich

In 1975 ten European member states of Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom founded the European Space Agency (ESA), with the ambition to create a space capability that didn’t rely on the US, and to consolidate space technology across Europe. Because of Britain’s recent successes; with the development of UK’s ‘Ariel 1’ that was devised to carry out solar science experiments (where subsequently five further Ariel satellites were constructed), and the development of the satellite launcher ‘Black Arrow’ which was based on its earlier test rocket, ‘Black Knight’ that successfully released the satellite ‘Prospero’ into low-Earth orbit, Britain found itself at the forefront of the collaboration, supplying much of ESA’s original technology and expertise.

Various successes followed:

In 1986, the ESA’s ‘Giotto spacecraft’ flew within 600km of Halley’s comet, becoming the world’s first spacecraft to study a comet up close.

In 1991, as the UK had no government-funded human spaceflight programme, a private consortium was formed called ‘Project Juno’ to raise money to pay the Soviet Union for a seat on a Soyuz mission to the Mir space station, alongside two Soviet cosmonauts. A call for applicants was publicised in the UK reading: ‘Astronaut wanted. No experience necessary’. A 27-year-old British chemist named Dr. Helen Sharman was selected from 13,000 applicants and trained intensely for 18 months in Roscosmos’ Star City, and subsequently became Britain’s first astronaut, spending 7 days, 21 hours, and 13 minutes in space, aboard the Mir space station.

image credit: Getty Images

In 1997 the hugely successful ‘Cassini-Huygens spacecraft’ was launched towards Saturn, via a flyby of Venus, and in 2003 the ESA launched the British lander ‘Beagle 2’ tasked with searching for signs of life on Mars. Sadly, confirmation of a successful landing was not forthcoming, and two months later, it was declared lost. But, eleven years later in 2015, the Beagle 2 lander was spotted by NASA’s ‘Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter’. Images hinted the lander’s solar panels had not deployed fully, masking its radio antenna needed for communication with Earth. But the lander appeared intact, proving it did successfully land on Mars.

image credit: NASA HiRISE/Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter/University of Leicester

In 2014, the ESA’s fourth cornerstone mission; ‘Rosetta’, achieved arguably space exploration’s most momentous feat, with British scientists and engineers again playing an integral role, namely British born Matt Taylor as the Project Scientist. On the 12 November, Rosetta’s ‘Philae lander’ touched down on comet 67P after a ten-year journey through the Solar System, 450 million km from the Sun, and rightfully held the world’s attention.

Since 1983, the ESA had been sending European astronauts, alongside NASA astronauts and Russian cosmonauts to the International Space Station (ISS), and in 2009 it selected its first ever British recruit: Army Major and test pilot Timothy Nigel “Tim” Peake, chosen from 8,413 applicants.

image credit: BBC

Tim’s Principia mission to the ISS (the name refers to Isaac Newton’s world-changing three-part text on physics, Naturalis Principia Mathematica, describing the principal laws of motion and gravity) began on the 15th of December 2015, in which the science museum welcomed 11,000 visitors that day, to watch the launch as it happened, and to celebrate the occasion in wishing the ESA’s first British astronaut a safe journey. After a hugely successful six months aboard the ISS, conducting numerous experiments, joining NASA astronaut Tim Kopra on a spacewalk to repair a faulty unit that regulates power from the solar panels, and even running the London Marathon, Major Tim Peake returned to Earth in the Soyuz TMA-19M descent module six months later, on the 18th of June 2016.

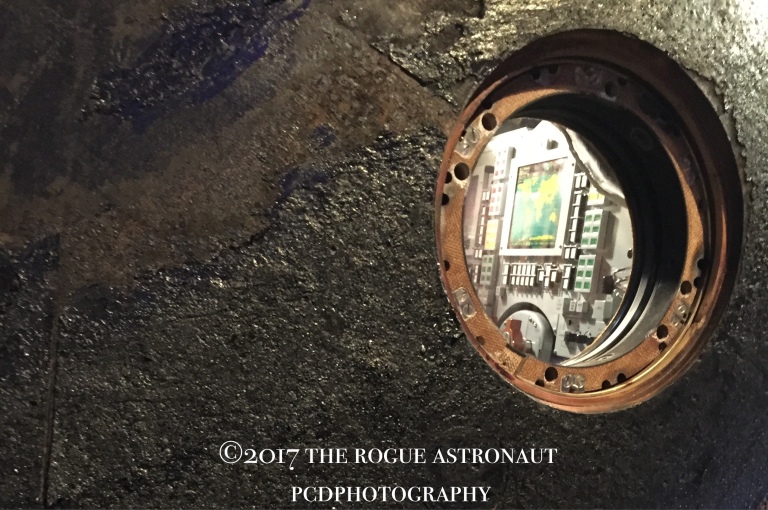

The descent module that brought Major Tim Peake, Colonel Tim Kopra, and Colonel Yuri Malenchenko home has been unveiled at the Science Museum in London where it will now be on permanent display, complete with scorching and charring on its heat-resistant skin from its re-entry through the Earth’s atmosphere, and main parachute, all 10,764 square feet of it. TMA-19M is the first flown, manned spacecraft in the UK’s national space technology collection. (The Apollo 10 Command Module, CM-106, that sits on display almost opposite to TMA-19M, is ‘on loan’ to the London Science Museum by the Smithsonian Institution, and therefore isn’t owned by the UK’s national space technology collection.)

image credit: ESA–Stephane Corvaja

Exploring the science museum less than 24-hours after the unveiling, (in which it was also announced that Major Tim Peake would be returning to the ISS sometime in 2019 for what would be his second mission to space) I spend several hours viewing the incredible objects in their collection and exhibitions, along with many of their artefacts of scientific achievements that are still making headlines today. I exit the ‘exploring space’ gallery and I find myself offering the Apollo 10 Command Module a nod of acknowledgement, a tip of my hat if you will (if I was wearing a hat) when passing it, as if seeing an old friend. And then, pride of placement in the Wellcome Wing of the museum, under the main parachute that’s suspended from the ceiling, there she is. TMA-19M. Major Tim Peake’s descent module.

This spacecraft inspires awe and challenges description.

It’s been in space. It has been docked to the ISS and continuingly orbited our planet, for six months straight. To put that into perspective; that’s around 400,000 miles travelled each day, 74 million miles over the duration of its mission. To get into orbit its Soyuz rocket had to accelerate it to 17,000 mph, the very same speed it travelled on its descent as it hurtled back through the Earth’s atmosphere, heated to more than 1500°C. After a four-hour journey, the craft safely and successfully parachuted down onto the plains of Kazakhstan. A film shown as part of the information provided shows the plumes of dust thrown up by the rockets’ exhausts as it touched down.

The Soyuz is a staunch, and dependable instrument of human spaceflight. And now, since the de-commissioning the Space Shuttle, is the only means of transporting humans both to and from the ISS. Soyuz, meaning Union, is a series of spacecraft designed for the Soviet space programme by the Korolyov Design Bureau (now RKK Energia) during the 1960s. And it was RKK Energia who had readied TMA-19M for display. The Soyuz succeeded the Voskhod spacecraft and was originally built as part of the Soviet Manned Lunar programme, and is the most frequently used and most reliable launch vehicle in the world to date. It is so reliable, that at least one Soyuz spacecraft will be docked to the ISS at all times for use as an escape craft in the event of an emergency.

Now, as of the 27th of January 2017, this particular Soyuz descent module has touched down at the Science Museum after a 1554 mile journey from Moscow. The journey from Russia took several days to complete, which is considerably longer than the eight to ten minutes that it would have taken to cover the same distance if it were still in orbit, docked with the ISS. It takes me 1 hour and 42 minutes from my home to the science museum, door to door. 37.4 miles.

image credit: Reuters/BBC

It was the first time Major Tim Peake had seen the descent module since stepping out of it in June, and at the unveiling said:

“You do become very attached to your spacecraft because it definitely does save your life, and I’m absolutely delighted that my Soyuz spacecraft, the TMA-19M, is going to be returning here to the UK and may serve, hopefully, as inspiration for our next generation of scientists and engineers.”

The Science Museum is the most visited science and technology museum in Europe, and it’s not hard to see why. There are over 15,000 objects on display, including world-famous objects such as the Apollo 10 command module and Stephenson’s Rocket. Now, with the addition of Major Tim Peake’s TMA-19M descent module, used as recently as of June 2016, and that the Soyuz remains the frequent used and most reliable launch vehicle/human transport to date, we are made to realise how we have forgotten that Russia led the way, and that Russia was first, and first many times. First satellite in space (1957), first animal in orbit (1957), first man in space (1961), first woman in space (1963), first spacewalk (1965), first on Mars and Venus (both 1970s). Ultimately, America did get to the moon, but throughout the space race America might have been only weeks behind, but arguably, behind they stayed. Free entry.

title image credit: Agence France-Presse News Agency